Linux

What follows are notes on the Linux and POSIX APIs.

System Calls

System calls can negatively impact user-mode application performance by evicting user-mode cache entries.

Processors often have various protection levels. For example x86 has 4, where ring 3 is the lowest privilege (for applications) and ring 0 is the highest privilege (for operating systems). Some instructions trap into the operating system which swtiches to ring 0, which can access all resources and execute all instructions.

Processors often also have various protection modes. For example x86 has root and non-root modes, each of which has the 4 protection levels state above. The root mode allows everything, while non-root mode has restrictions.

Files

Each process has its own file descriptor table. Each entry in that table contains:

- set of flags controlling the operation of the file descriptor, for example close-on-exec

- reference to the open file description.

The kernel maintains a system-wide open file table of all open file descriptions, also known as open file handles. Each entry contains

- the current file offset

- the status flags, i.e. flags passed to

open() - file access mode (read-only, write-only, or read-write)

- signal-driven I/O settings

- reference to the inode object for the file

Then each file system has a table of inodes for all files on the file system, where each entry contains:

- file type (e.g. regular, socket, FIFO) and permissions

- pointer to list of locks held on the file

- file properties (e.g. size, timestamp)

There can be multiple file descriptors associated with a single file in a single process either by duplicating file descriptors with dup() or dup2(), or inheriting them after a fork(). This causes them to point to the same open file description, which means that they both use and update the same file offset and status flags.

There can also be multiple file descriptors associated with the same file that do not share the same open file description by making separate calls to open().

Scatter-Gather I/O

The pread() and pwrite() functions can be used to read or write at an explicit offset, without consulting or updating the actual file offset.

The readv() and writev() functions can be used to perform scatter-gather I/O. They each take a structure that specifies a list of positions to write to or read from respectively, and how much. For example, the readv() function reads a contiguous sequence of bytes from a file into the buffers specified. There are also preadv() and pwritev() variants which take an explicit offset.

File Atomicity

The system can provide certain atomicity guarantees. The O_EXCL flag for open() ensures that the caller is the creator of the file. The O_APPEND flag ensures that multiple processes appending data don’t overwrite each other’s output 1.

File Buffering

File buffering occurs at the kernel level as well as the standard library level of many languages, including C and C++’s.

Disk buffer caches are caches that reside in main memory and are used to cache disk data. Data is read from and written to the disk buffer cache, which is periodically flushed to disk.

The fsync() call causes the buffered data and all metadata associated with the file descriptor to be flushed to the disk, forcing a synchronized I/O file integrity completion state. The fdatasync() call on the other hand causes only the buffered data to be flushed to the disk, forcing a synchronized I/O data integrity completion state. Using fdatasync() can be much faster if the metadata isn’t as important, because the metadata and the data are usually stored on different parts of the disk.

The sync() call causes all kernel buffers containing updated file information (both data and metadata) to be flushed to disk. On Linux, this call returns until the data has been transferred to the disk or its cache.

The posix_fadvise() call can be used to advise the kernel about the likely file access patterns. For example, if it is advised about random access, then Linux will disable file read-ahead.

File Systems

Devices are represented by entries in the /dev directory, and each device has a corresponding device driver which implements the standard operations such as read() and write().

A character device is one that handles data on a character-by-character basis, such as terminals and keyboards. A block device is one that handles data a block at a time, where the block size depends on the type of device.

Hard disk drives store data on the disk on concentric circles called tracks, which are divided into sectors each containing a series of physical blocks.

The seek time is the time it takes for the disk head must to move to the appropriate track. The rotational latency is the time it takes for the appropriate sector to rotate under the head. The transfer time is the time it takes for the blocks to be transferred.

I/O scheduling aims to schedule disk access operations so as to reduce disk head movement. This is accomplished by striving to maximize sequential accesses over random accesses, possibly by reordering disk accesses so as to coalesce (nearly) sequential accesses together before jumping to random accesses. For example, the sequence “write block 25, write block 17” can be reordered to “write block 17, write block 25.”

Disk prefetching refers to prefetching more than one block when reading so as to increase cache hits by leveraging locality, similar to how a CPU reads an entire cache line is read at a time from main memory.

Disks are divided into partitions, each of which may contain a file system. Each file system contains an inode (i.e. index node) table and there is one entry for each file on the file system, each entry containing metadata such as:

- file type

- user and group owners

- access permissions

- timestamps

- hard link count

- byte size

- allocated block count

- pointers to data blocks

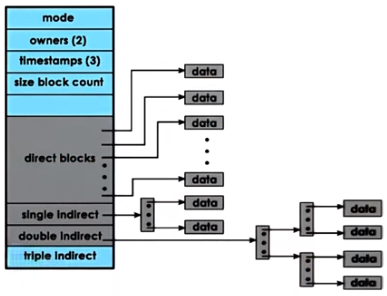

Since inodes contain pointers to data blocks and an inode’s size is fixed, inodes inherently limit how many data blocks there can be, and by extension they limit the maximum size that a file may be. This maximum can be increased by using indirect pointers, which are pointers to other blocks that are full of pointers to data blocks. There can be multiple levels of these indirect pointers, similar to a hierarchical page table, essentially creating a tree.

A superblock is an abstraction that provides file system-specific information regarding the file system’s layout. It maintains an overall map of all disk blocks, specifying whether each block is an inode, data, or free.

Journaling file systems are ones keep a write-ahead-log (WAL) for metadata updates (and optionally data updates) before the actual file updates are actually performed, which makes the data more resilient in the event of a crash. This also means that a file system check is not required after a system crash. Each entry may contain the block, offset, and value to write. Entries are periodically committed (written) to disk.

I/O overhead is mitigated by caching/buffering to reduce the number of actual disk accesses, I/O scheduling to reduce disk head movement, prefetching to increase cache hits, and journaling to reduce random access 2 and prevent data loss.

File systems are all mounted under a single directory tree represented by the root / at specific locations known as mount points. The virtual file system (VFS) is an abstraction, a unified representation of a single file system, even if there are multiple different file systems mounted at different points.

A bind mount allows a file or directory to be mounted at multiple locations in the file system. Unlike hard links, bind mounts can cross file-systems and chroot jails, and it’s possible to create a bind mount for a directory.

Directories

Stored in the file system as a regular file except they are marked differently in their i-node entry and their data content is a table mapping filenames to i-node numbers.

Hard Links

Hard links are also referred to simply as ’links’. It is soft links which require additional qualification. Links can be created using the ln command which is often used to instead create soft (symbolic) links (ln -s). Creating a hard link to a file doesn’t copy (cp) the file itself, instead it creates a different filename pointing to the same i-node number and also increases the ’link count’ of the file. This can be verified by running ls -li to see each file’s corresponding i-node number and link count.

Hard links can’t be made to directories, thereby preventing circular links. The book recounts how early UNIX implementations did allow this in order to facilitate directory creation. mkdir didn’t exist, so directories were created with mknod and then links were made for . and .. to facilitate directory traversal. It also reminds the reader that ’links to directories’ are more or less possible with bind mounts.

Shared Pointers

Hard links remind me of shared_ptr in C++11. I can imagine a scenario in which different processes need access to a common file but the common file needs to be deleted when all processes are finished with it. They can create a link to the file and use that to do their work, since it will be the same file as the original. When they are finished with the file, they can unlink (i.e. remove the link) to the file. The file system will automatically delete the file itself when the number of links has reached zero. I don’t know if this is common—or even a correct—practice, nevertheless I immediately thought of this when I came across links.

Temporary Files

A trick in the spirit of the above is touched upon by the book. It talks about how a program might sometimes create a file, unlink it immediately, and then continue using the file knowing that the file will be destroyed 1) explicitly when the file descriptor is closed or 2) implicitly when the program closes. This is what tmpfile does.

Symbolic Links

Also known as soft links, these types of links are more commonly used by people. They simply consist of the type i-node field being set to symlink and the data blocks of the i-node set to the target path.

An interesting note discussed by the book is that some UNIX file systems (such as ext2, ext3, and ext4) perform an optimization where, if the target path can fit in the part of the i-node that would normally be used for data-block pointers, the path is simply stored there instead of externally. In the case of the author, the ext filesystems appropriate 60 bytes to the data-block pointers. Analysis of his system showed that of the 20,070 symbolic links, 97% were 60 bytes or smaller.

Directory Streams

Directory entries can be enumerated by getting a directory stream handle with opendir (or fdopendir to avoid certain race conditions) and pulling directory entries dirent from the directory stream with readdir.

Additionally, recursive file tree walking can be achieved using nftw (new file tree walking) by passing it a callback to call on every entry.

Working Directories

The working directory (getcwd) of a process determines the reference point from which to resolve relative pathnames within the process. For example if the working directory is /home/user then a a file path of ../user2 will refer to /home/user2. Simple stuff. The working directory can be changed with chdir and fchdir.

Aside from this, Linux (> 2.6.16) provides various *at() calls, such as openat, which operate relative to a directory file descriptor. These calls (now part of SuSv4) help avoid certain race conditions and help facilitate an idea of “virtual working directories” which is particularly useful in multithreaded applications since every thread shares the working directory attribute of the process.

Root Directories

Every process also has a root directory which serves as the reference point from which to resolve absolute pathnames (as opposed to relative pathnames with working directories). This is usually /, but can be changed with chroot, which is often used to create so called “chroot jails”, something FTP servers might do to limit a user’s filesystem exposure to their home directory. One thing to remember to do is to change the working directory to the chrooted path, in effect “stepping into the jail.” Otherwise the user is able to continue roaming around outside the jail.

chroot jails aren’t a silver bullet. Some BSD derivatives provide a systemcall, jail, that handles various edge cases.

I/O Devices

I/O devices typically have a variety of features such as control registers, which are registers that are accessed by the CPU to allow CPU⟷device interactions. Command registers are registers that can be used to control what the device does. Data registers are registers that control data transfer into and out of the device. Status registers are registers that can be used to find out what’s happening on the device. A microcontroller is like the device’s CPU and it processes the actual device operations.

The CPU and devices communicate via an interconnect such as Peripheral Component Interconnect (PCI). In particular, PCI makes devices accessible in a manner similar to how CPUs access memory, so that device registers appear to the CPU as memory locations at a specific physical address. When a CPU writes to such a memory location, the PCI controller will route that particular access to the appropriate device.

The memory-mapped I/O model consists of dedicating part of the host physical memory for device interactions. The base address registers (BAR) control which region of memory is dedicated to device interactions, specifically, how much memory and starting at which address. Base address registers are configured during the boot process.

The I/O port model consists of using dedicated in/out CPU instructions to send and receive data from a particular device. The target device is the I/O port and the value to write or read is specified in a register.

Communication from device to CPU can be initiated when the device interrupts the CPU or the CPU polls the device status registers. Device interrupts can be generated as soon as possible, but interrupt handling has overhead, complexity, and causes cache pollution. CPU polling of device state can be chosen at a convenient time by the CPU, but there is a delay in responding to the event as well as CPU overhead if there is constant polling.

Programmed I/O (PIO) is an I/O interaction method that requires no additional hardware support, in which the CPU “programs” the device by writing into its command registers and controlling data movement by accessing its data registers. PIO can be inefficient because it could require many I/O operations in order to exchange a lot of data.

Direct Memory Access (DMA) requires special hardware support in the form of a DMA controller, and works similar to PIO in that the CPU programs the device via its command registers, but the data to transfer is specified via the DMA controls by specifying the in-memory address and size of the buffer to send. For this to work, the memory in the buffer needs to remain there in physical memory until the transfer completes, which can be accomplished by pinning the pages so that they’re not swapped to disk.

Since DMA has an upfront setup cost, PIO can be more efficient for very small payloads.

Operating system bypass for I/O allows the user-level to directly access the device registers and data. This requires device support in the form of extra registers for it to give to additional user processes and the operating system, as well as demultiplexing support for determining which processes to respond to. This requires a “user-level driver” which is often a library. The kernel retains coarse-grain control, such as enabling and disabling of the device.

Memory

Memory latency is even more of an issue in shared memory systems because there is contention on the memory, which further increases latency.

There are a few policies the CPU can adopt when writing to memory with respect to updating the actual data in memory:

- no-write: cache is bypassed and any reference to that address in the cache is invalidated

- write-through: write is applied to both cache and memory

- write-back: write to the cache and eventually write to memory when the cache line is evicted

A Non-Cache-Coherent (NCC) architecture is one where multiple copies of the same data in multiple CPU caches can diverge if one of the CPUs modifies it. This divergence must be remedied in software.

A Cache-Coherent (CC) architecture is one where the hardware ensures that the caches remain coherent, so that if one cache is updated, any other caches with copies of the same data do not diverge by keeping stale copies.

The write-invalidate (WI) cache-coherence strategy works by invalidating the cache entries of other CPUs which had copies of the updated data.

The write-update (WU) cache-coherence strategy works by updating the cache entries of other CPUs with the new data.

Write-invalidate has a performance benefit over write-update because only the address of the data has to be sent to the other caches for them to invalidate the corresponding entries. As a result, future writes to the same value on the original CPU will not trigger additional communications to the other caches, since the entries will no longer exist on the other caches.

On the other hand, write-update has the benefit that the updates are immediately available on the other CPU caches, whereas with write-invalidate the other CPUs must access main memory in order to obtain the latest value.

To ensure cache coherence, atomic operations will always issue to the memory controller, completely bypassing caches. This ensures that all operations are ordered and synchronized 3. A consequence of this is that atomic operations take longer due to memory latency and contention, and they generate coherence traffic to update or invalidate cache references in order to preserve coherence, even if the value didn’t change. In total, bus/interconnect contention, cache bypassing, and coherence traffic cause atomic operations to be especially expensive on shared memory processor architectures.

Virtual Memory

Virtual addresses are considered virtual because they don’t have to correspond to actual locations in physical memory.

Virtual addresses decouple the process data layout (virtual memory) from the physical memory layout, so that it doesn’t matter how the compiler chooses to lay out the program data.

Internal fragmentation refers to gaps within a sparsely populated page leading to wasted space. External fragmentation refers to non-contiguous holes of free memory which can prevent continuous memory allocations of that size from being allocated.

In order to minimize external page fragmentation, it’s important to coalesce/aggregate free areas, in order to increase the size of the holes.

There is a trade-off with respect to the virtual page size: a larger page size means fewer page table entries which means smaller page tables, which means more TLB hits. However, larger page tables increases the likelihood of internal fragmentation which results in wasted memory, because even a small memory allocation might allocate an entire large page for it.

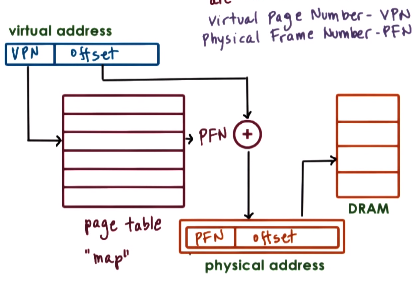

Page tables maintain a mapping between virtual addresses and physical addresses. Specifically, it maps the virtual page number (VPN) to the physical frame number (PFN), that is, the first virtual address in a page to the first physical address in a page frame. This is sufficient instead of needing the entire virtual and physical addresses because the page table maps pages, not individual addressable units; an offset can be used to index within the actual page frame.

A page table exists for each and every process. On a context-switch, the page table pointer is updated by updating the page table register, which points to the currently active page table (e.g. CR3 on x86), to point to the new process’ page table.

The number of page table entries is all of the virtual page numbers that can exist in a virtual address space, which is $2^{N} / M$ where $N$ is the virtual address size and $M$ is the page size. For example, on a 32-bit architecture with 4 KB page size, that means that $N = 2^{32}$ and $M = 4096$, so $2^{32} / 4096$ = 1,048,576 virtual page numbers (and thus, one page table entry for each one).

This means that there would need to be 1,048,576 entries in a page table, where each entry would contain for example 4 bytes to store the page frame number and additional bits. This amounts to $1,048,576 * 4\ \text {bytes}$, or about 4 MB per-process.

On a larger virtual address space, such as a 64-bit system, the virtual address space would be $2^{64}$ with a page table entry of 8 bytes and a page size of 4096 bytes would amount to $2^{32} / 4096 * 8\ \text {bytes}$, or about 36 petabytes per-process. This is clearly prohibitively expensive, especially considering that the vast majority of the address space is unused, meaning that the vast majority of the page table entries are not necessary.

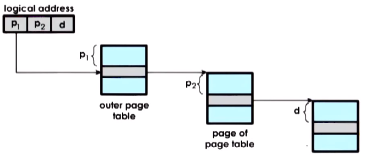

For this reason, a level of indirection is introduced in order to facilitate a sparse page table. Specifically, an outer page table contains pointers to internal (real) page tables. The internal page tables are only created for valid virtual memory regions, allowing holes to exist.

This is known as a hierarchical page table. It is indexed by:

- obtaining the virtual address prefixes

$p_1$and$p_2$and the offset$d$. - index into the outer table with

$p_1$to obtain the internal page table - index into the internal page table with

$p_2$to obtain the page - index into the page with the offset

$d$to obtain the physical address

The actual virtual-to-physical address translation is done by hardware (the MMU), which means that the hardware has certain expectations about the structure of the tables, and consequently dictates what kinds of memory management modes are supported, the kind of pages there can be, and the virtual and physical address format.

More table levels can be introduced but there is a trade-off. More table levels means smaller internal page tables, increasing the likelihood that the virtual address space has gaps that match the needed granularity. However, more table levels means that more memory accesses are required per translation, increasing translation latency.

Page tables can also contain a validity bit (aka presence bit) which specifies whether the access represented by the mapping is valid, e.g. whether the content of the virtual memory is actually present in physical memory.

A valid bit of 1 means that the page is indeed in memory and the mapping is valid. A valid bit of 0 means that the page is not in memory. In this case, the MMU will raise a fault. If the MMU determines that the mapping is invalid, then it decides if the access should be permitted, where the page is actually located (e.g. on disk), and where the physical memory should be placed. More specifically:

- MMU generates an error code on the kernel stack

- MMU generates a trap into the kernel, triggering a page fault handler

- Page fault handler determines action based on error code and faulting address. It can decide to bring the page from disk to memory or send a

SIGSEVsignal if there is a protection error.

Since virtual memory is often much larger than physical memory, there’s a possibility that a virtual memory page is not present in physical memory. Demand paging allows pages to be swapped in and out of memory and a swap partition on the disk, which handles this situation.

A page can be pinned to physical memory so that it won’t be swapped to disk. This is useful for when interacting with devices via direct memory access (DMA).

If the MMU determines that the access is invalid but the virtual address is valid, the mapping will be re-established on re-access between the valid virtual address and a valid physical address.

Page tables can also contain a dirty bit which represents whether the page has been written to. This can indicate that the cache needs to be flushed to disk.

Page tables can also contain an access bit which represents whether the page has been accessed at all (i.e. read or write).

Page tables can also contain protection bits which specify whether the page can be read, written, and/or executed (RWX). For example, on x86, the R/W bit set to 0 means that it’s read-only, and 1 means its’ read-write. The U/S bit specifies whether the page is accessible from user-mode (0) or supervisor-mode only (1). The MMU would then check these bits to determine the validity of a page access.

The translation look-aside buffer (TLB) is a cache of valid virtual-to-physical address translations kept by the MMU. The TLB also contains protection and validity bits, like the page tables do. If there’s a TLB (cache) miss, then the translation is made by consulting the page table. Even a small number of addresses cahced in the TLB results in a high cache hit-rate when there is high temporal and spatial locality of memory addresses.

To convert a virtual address to a physical address, the virtual page number of the address is used to index into the page table to obtain the physical frame number. Then the virtual address’ offset if concatenated to the physical frame number to arrive at the complete physical address.

A common operating system optimization is allocation on first touch, where the memory for a virtual address space is allocated until it’s first accessed.

The kernel decides which parts of the address space and allocated and where. If a portion of the process address space is on disk and is required, it will be swapped into physical memory, potentially causing another portion that was previously in physical memory to be moved to the disk. Conversely, if some pages are going unused, they may be swapped out to disk to allow other data to use that memory.

Specifically, a page(out) daemon swaps out pages when memory usage is above some threshold (the high watermark) or CPU usage is below some threshold (low watermark). The pages chosen for swapping out should be those that can’t be used (e.g. due to some LRU policy, determined by access bit) and those that don’t need to be written out (determined by dirty bit), while avoiding non-swappable pages containing important kernel state, I/O operations, etc.

Shared memory IPC is facilitated by mapping certain virtual addresses from each participating process to the same physical addresses.

Page frames are chunks of physical memory the same size as virtual pages. A page frame essentially “contains” a virtual page, just like a cache line holds a cache block.

A memory management unit (MMU) is a hardware component that receives virtual addresses from the CPU and translates them into physical addresses. An MMU may report a fault for any of:

- an access is illegal (e.g. physical address hasn’t been allocated)

- permissions aren’t satisfied for this access

- referenced page isn’t present in memory and must be fetched from disk

A user-level memory allocator is responsible for the dynamic process state, such as the heap.

A kernel-level memory allocator is responsible for allocating memory regions for the kernel as well as the static state of a process, such as the code, stack, and initialized data regions, as well as keeping track of the free memory that’s available on the system.

The kernel-level buddy allocator works by starting with $2^x$ chunk of pages. On each request, one of the chunks is subdivided into another $2^y$ chunk until the smallest such chunk is found that can satisfy the request. When freeing, the “buddy,” the adjacent chunk, is checked to see if it’s also free in order to aggregate them both into a larger chunk.

In the example above, an allocation request of size 8 is received. The region is subdivided until a chunk of size 8 is found to allocate. Then another chunk of size 8 is allocated (on the buddy of the previously allocated chunk). Then an allocation request of size 4 is received which requires subdividing other chunks. Then the second allocated chunk of 8 is deallocated and its buddy is checked to see if it’s free in order to merge with it, but it’s not. Then the first allocated chunk of 8 is deallocated and its buddy is checked to see if it’s free in order to merge with it. It is, so they merge into a chunk of 16.

Since the buddy allocator specifically allocates at a $2^x$ granularity, it increases the likelihood of internal fragmentation, since not a lot of kernel data structures are near the size of a power of 2.

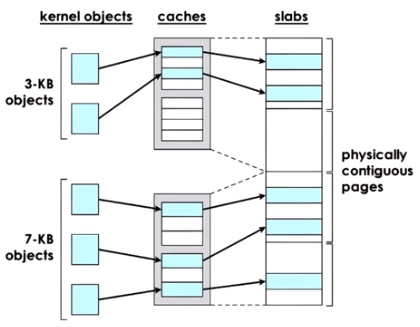

The kernel-level slab allocator works by using object caches backed by physically contiguous pages, or slabs, of a size that is a multiple of the object size.

Checkpointing is the process of taking a snapshot of a running application in order to resume it at a later point or transfer it to another machine. This can work by Copy-on-Write’ing the process’ virtual memory and then periodically storing diffs of the dirtied pages for incremental checkpoints.

Processes

Each process has a system-wide process ID known as a PID. A process can obtain its PID via getpid(). Each process has a parent process, whose ID can be obtained via getppid().

The setcontext() family of functions can be used to save and load execution contexts, which can be used to implement coroutines, iterators, and fibers.

The process control block (PCB) is a data structure maintained by the kernel for each process. It contains process state such as:

- process ID

- program counter (PC)

- registers

- memory limits

- list of open files

- priority

- signal mask

- CPU scheduling information

Forking a process causes the PCB to be copied so that both processes continue executing at the instruction after the fork.

Credentials

Each process may have many sets of user and group identifiers (UIDs and GIDs):

- real user ID and group ID

- effective user ID and group ID

- saved set-user-ID and saved-set-group ID

- file-system user ID and group ID (Linux-specific)

- supplementary group IDs

The real user ID and real group ID identify the user and group to which the process belongs, and these are inherited from the parent process, all the way back to the IDs read by a login shell from /etc/passwd.

The effective user ID and effective group ID are the IDs consulted to determine the permissions granted to a process when it tries to perform certain operations. These are also used to determine whether a process can send a signal to another.

If a process’ effective user ID is 0, which is the UID of root, then it has all of the privileges of the superuser, making it a privileged process.

A set-user-ID program is one which can set its effective user ID to the same value as the user ID (i.e. owner) of the executable file; same with set-group-ID. This is done by way of two special permission bits on an executable file: the set-user-ID and set-group-ID bits. These can be set via chmod for files a user owns or for any file if the user is privileged.

When a set-user-ID program is run, its effective user ID is set to be the same as the user ID of the program’s file, and likewise in the case of set-group-ID. For example, if the file is owned by root then the program’s effective user ID becomes that of root, making it a privileged process.

It’s also possible to use set-user-ID to grant a program access to a particular resource, for example by creating a special-purpose user which has access to that file and setting the set-user-ID bit. This has the benefit of not giving it full, broad superuser privileges.

the saved-set-user-ID and saved-set-group-ID is a saved copy of the effective user ID and effective group ID after having loaded the set-UID and set-GID, if those bits were set, in which case it’s a saved copy of the set-UID and set-GID. These saved copies allow certain system calls to switch between the saved-set-UID and the real UID, for example, allowing privileges to be temporarily dropped or regained, which is a good security practice.

The file-system user ID and file-system group ID are used on Linux instead of the effective user ID and effective group ID equivalents to determine the permissions of a process when performing file-system operations—otherwise the effective IDs are used for all other operations. However, usually the file-system IDs are identical to the effective IDs; the only differ when explicitly made to via setfsuid() and setfsgid().

The supplementary group IDs are additional groups to which a process belongs which are inherited from its parent.

Execution Time

The kernel separates CPU time used by a process into user time (also known as virtual time), which is the amount of time executing in user mode, and system time, which is the amount of time spent executing in kernel mode, i.e. executing system calls or servicing page faults for the program.

Creation

The fork() call creates a new process (child) by making an almost exact copy-on-write duplicate. A new process can be executed via exec(), which modifies the process’ virtual memory with that new process’ data.

Copy-on-Write (COW) refers to write-protecting the original page and mapping the new process’ virtual address to it. Then if the original page is written to, a page fault occurs, the page is copied, and the page table is updated so that the virtual address points to the copy.

There is no guarantee about whether the parent or child continues first after a call to fork(), so it should generally be called as a condition to a switch statement for example:

pid_t childPid;

switch (childPid = fork()) {

case -1:

// error

case 0:

// child

default:

// parent

}

After the fork, the child receives duplicates of all of the parent’s file descriptors, made in the same manner as dup(), referring to the same file, file offset, and open file status flags. Further, if one updates any of these, the changes are visible to the other.

Termination

Orphaned children are adopted by init. When a child terminates before a parent has a chance to call wait(), the kernel turns the child into a zombie, which means that most of the resources held by the child are released back to the system: only the child’s process Id, termination status, and resource usage statistics are preserved. Zombies can’t be killed by signals in order to ensure that a parent can always eventually perform a wait(). When the process finally performs the wait(), the kernel removes the zombie since that information is no longer required. If instead the parent terminates before it ever performs a wait(), then init adopts the child and performs a wait() so that the zombie can be removed. If the parent doesn’t terminate but also never performs a wait(), then the zombie entry will remain, taking up resources.

Execution

The exec() family of functions can be used to replace the currently-running program with a new program. All file descriptors open by the previous program remain open. This is something used by the shell for example for I/O redirection. Signal dispositions are reset because the signal handlers reside in the text region of the previous process, which is now gone and replaced with the new process.

Threads

Threads share the same virtual address space (e.g. code, data, files), but they have separate execution contexts, so they need a separate stack, registers, etc. The increased sharing increases cache utilization.

It can be beneficial to have more threads than CPUs if the threads otherwise wait on I/O and the wait is longer than context-switching twice (away and back), then the kernel can context-switch to another thread in order to remain busy.

It’s faster to context-switch threads than context-switching processes because of the amount of data that threads share, including virtual address space, so the virtual address mappings don’t have to be updated as they would have to be when context-switching to an entirely different process.

A detached thread is one that has become detached from its parent, so that it can continue executing even after the parent exits. This means that the parent can no longer join the child. When the child wants to exit, it can simply call pthread_exit().

In the many-to-one threading model, the user-level thread management library decides which user-level threads are mapped to individual kernel-level threads. This means that the kernel has no insights into application needs. For example, the kernel could block the entire process if one user-level thread blocks on I/O, since that would block the entire kernel-level thread on to which the process’ threads are mapped onto.

Also, with the process-scope of multi-threading, the kernel isn’t aware that the process has many threads, so it ends up giving it the same amount of resources as if it only had one thread, which can negatively impact performance.

User-level thread stacks often contain a red zone which is a region of memory at the end of the stack region which is configured so that if a thread’s stack grows into the red zone region, a system fault is triggered, preventing the stack from overflowing into the next user-level thread’s data structure.

Thread library implementations may avoid outright destroying threads because thread destruction and subsequent thread creation is relatively expensive. Instead finished threads are placed on “death row,” i.e. marked to be destroyed but not actually destroyed. If another thread is requested for creation and a marked thread exists, its data structures are re-used in order to avoid re-allocation. Otherwise, a reaper thread periodically destroys marked threads.

Designated threads can be used for blocking I/O operations in a situation where there are no asynchronous equivalents and blocking the main thread(s) is not viable.

Scheduling

The CPU scheduler determines which one of the currently ready processes will be dispatched to the CPU to begin execution and how long it should run for. Process preemption refers to interrupting the currently running process and saving its current context.

In order to run a different process, the operating system must preempt the current process and save its context, then choose the next process based on the scheduling algorithm, then dispatch the new process and load its context.

A timeslice is the maximum amount of uninterrupted time given to a task, aka a quantum.

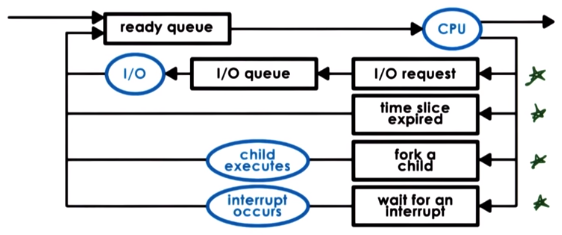

A process can be deferred and placed on a ready queue if:

- it performs an I/O request

- its timeslice expires

- it’s forked

- it’s waiting for an interrupt

Run-to-completion scheduling refers to running a process to completion once it’s scheduled onto a CPU.

First-come, first-serve (FCFS) scheduling works by scheduling tasks onto CPUs in the same order in which they arrive on the run-queue.

Shortest Job First (SFJ) scheduling works by scheduling tasks in order of their execution time duration, shortest first. The duration of a task can be based on heuristics or previous executions.

Preemptive scheduling refers to a scheduling policy in which processes can be interrupted. To facilitate this, the scheduler should be invoked whenever a new task arrives on the run-queue.

Round-robin scheduling works by picking processes from the front of a run-queue, similar to first-come first-serve (FCFS) except that processes don’t run to completion. Instead, processes may yield to others, such as when waiting on I/O.

Priority scheduling works by running the highest-priority task next. Priority aging is a way to mitigate process starvation of low-priority processes in priority scheduling. It specifies that the priority of a process is a function of its actual priority and the amount of time it has spent in the run-queue, so that the more time it has spent in a run-queue, the higher priority it has.

Priority inversion is a condition in which the priority of threads effectively becomes inverted because a high-priority thread requires a lock held by a low-priority thread. The high-priority (e.g. 1) thread gets scheduled, but the low-priority (e.g. 3) thread still holds the lock, so it suspends to continue waiting and another low-priority (e.g. 2) thread is scheduled instead since it’s of higher priority than the lock-holding thread. This prevents the lock-holding thread from completing its critical section and thus starves the high-priority thread, effectively “inverting” the priority levels of the high-priority 1 thread and the lower-priority 2 thread.

One solution to priority inversion is priority inheritance: temporarily boost the priority of the lock-holding thread to essentially the same level as the higher-priority thread contending the lock. This prevents other lower-priority threads from getting scheduled before the high-priority task. Also see random boosting.

CPU-bound tasks prefer longer timeslices to avoid/amortize the overhead of context-switching on timeslice boundaries, keeping high CPU utilization and high throughput.

I/O-bound tasks prefer shorter timeslices because they’re able to issue and respond to I/O operations earlier/quicker.

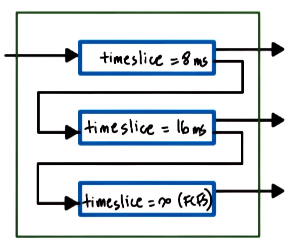

A Multi-Level Feedback Queue is a run-queue data structure that adaptively gives different timeslices and scheduling policies to different processes based on their needs. For example:

- new tasks enter the top-most, shortest timeslice queue

- if the task yields voluntarily, it’s kept at the same timeslice level

- tasks in lower queues get priority boosts when repeatedly releasing the CPU due to I/O waits

Cache affinity refers to keeping a task on the same CPU as much as possible in order to keep that cache hot. This can be achieved by scheduling processes so that there are per-CPU run-queues and schedulers onto which processes are load-balanced. The per-CPU schedulers try to repeatedly schedule tasks onto the same CPU. Load-balancing can be based on the per-CPU run-queue length, or when the CPU is idle it can steal work from other per-CPU run-queues.

Non-Uniform Memory Access (NUMA) refers to a system which has multiple memory nodes and access to the local memory node is faster than access to a remote node. NUMA-aware scheduling binds tasks to CPUs that are closer to the memory nodes containing the tasks’ states.

Hyper-threading (aka Simultaneous MultiThreading (SMT)) has multiple hardware-supported execution contexts within a single CPU, such as multiple sets of registers, enabling very fast context-switches. This can be used to hide memory access latency by quickly context-switching

O(1) Scheduler

The Linux O(1) scheduler has 140 priority levels. It separates process priority levels into two categories: real-time tasks with priority 0-99 and time-sharing tasks with priority 100-139. User processes have a default priority level of 120, but can change their priority anywhere in the range of 100-139 by specifying a nice value which is added to the priority level, which can be anywhere in the range of [-20, 19]. This way, the priority can be increased by specifying a negative nice value.

With the Linux O(1) scheduler, a process’ timeslice depends on its priority level: high-priority processes get longer timeslices and low-priority processes get shorter timeslices.

In order for the Linux O(1) scheduler to determine a process’ priority, it monitors the amount of time that a process spends sleeping (i.e. waiting/idling). A smaller sleep time means the process is compute-intensive, so the priority is shifted towards a lower priority by 5. A longer sleep time means that the process is interactive, so the priority is shifted towards a higher priority by 5.

The run-queue data structure for the Linux O(1) scheduler essentially has two arrays of 140 (one for each priority level) queues. There are two arrays because one is for active processes and the other is for expired processes whose timeslices have expired.

As each processes’ timeslice expires, it’s queued onto the corresponding queue in the expired array. However, if the process yields (e.g. to I/O) before its timeslice expires, it remains on the active array. Once all processes expire and there are no remaining processes in the queues of the active array, the the pointers to the active and expired arrays are swapped (like a double-buffer swap) and the process is repeated on the newly active array.

The Linux O(1) scheduler gets its name because it can achieve constant time $O(1)$ process selection by using a bitmap to index into the first (thus highest-priority) non-empty run-queue, and accessing the head of the run-queue is itself a $O(1)$ operation.

The Linux O(1) scheduler mitigates process starvation by ensuring that all tasks in the active array are run until their timeslices expire, including lower-priority tasks, which has shorter timeslices in order to minimize interfering with higher-priority tasks.

Completely Fair Scheduler

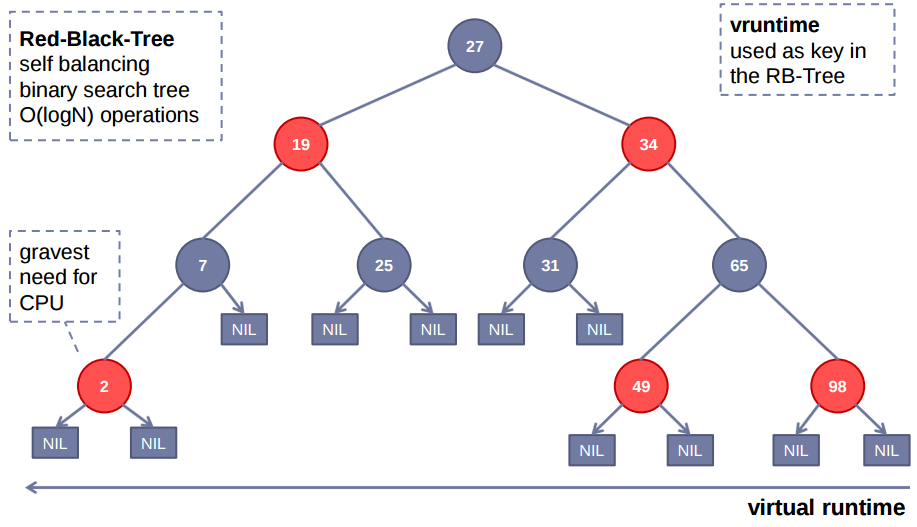

The Linux Completely Fair Scheduler (CFS) works by ordering processes by their virtual run-time (aka vruntime), which is the amount of time in nanoseconds that the process has spent running on the CPU. To keep processes ordered by vruntime, it uses a red-black tree. CFS always schedules the left-most node, the one which has spent the least amount of time running, by removing it from the tree and sending it for execution.

Periodically, CFS updates the current process’ vruntime and compares it to the left-most node in the tree. If the current process’ vruntime is less than the left-most node’s vruntime, the current process continues running. Otherwise if the current process’ vruntime is now greater than the left-most node’s vruntime, the current process is preempted and re-inserted into the red-black tree, and the left-most node is scheduled.

CFS handles priority and niceness by adjusting the progress rate of a process’ vruntime. In other words, low-priority processes will have a faster rate of increase in their vruntime, whereas high-priority processes will have a slower rate of increase in their vruntime. This has the effect that low-priority processes run for less time, because they more quickly reach the point at which the left-most process has a smaller vruntime than theirs, and vice versa.

The performance characteristics of CFS are determined by the performance characteristics of the red-black tree that backs it: $O(\text {height})$ for selecting a task and $O(\log n)$ for adding a task.

Concurrency

Strategies

The pipeline pattern consists of a sequence of stages, each processed by a single or group of threads, producing the result into the next stage’s work queue.

Mutexes

An adaptive mutex is one that acts as a spinlock if the critical section is short, otherwise it follows the regular behavior.

A spinlock is one that contiguously checks if the lock has been released, i.e. within a busy-loop, though not necessarily in the most naive way possible.

For example, a test-and-set spinlock can be implemented with:

spinlock_init(lock):

lock = FREE

spinlock_lock(lock):

while (test_and_set(lock) == BUSY) {

// spin

}

spinlock_unlock(lock):

lock = FREE

A test-and-test-and-set spinlock is one which doesn’t spin on the expensive atomic operation in the regular case that the lock is not free, which decreases memory contention. Instead it spins on the cached value, which will eventually be updated either due to write-update or because of write-invalidation. When a change is detected, the atomic operation is performed to determine if the lock can indeed be acquired 4.

However, the test-and-test-and-set spinlock also has some performance disadvantages because everyone sees that the lock is free at the same time, which causes everyone to try to acquire the lock at the same time. This creates $O(n^2)$ cache-coherence contention because each processor will attempt to acquire the lock via the atomic operation, which produces coherence traffic to invalidate all other caches.

A possible implementation could be:

spinlock_lock(lock):

while (lock == BUSY || test_and_set(lock) == BUSY) {

// spin

}

It’s possible to share pthread synchronization primitives like mutexes and condition variables by placing them in shared memory and initializing their attributes with PTHREAD_PROCESS_SHARED.

struct shm_data_struct_t {

pthread_mutex_t mutex;

char *data;

};

seg = shmget(ftok(arg[0], 120), 1024, IPC_CREATE | IPC_EXCL);

shm_address = shmat(seg, (void *)0, 0);

// cast shared memory segment pointer to struct

shm_ptr = (shm_data_struct_t *)shm_address;

pthread_mutexattr_t(&m_attr);

pthread_mutex_attr_set_pshared(&m_attr, PTHREAD_PROCESS_SHARED);

// initialize mutex residing in shared memory segment

pthread_mutex_init(&shm_ptr.mutex, &m_attr);

Condition Variables

Condition variable implementations need to keep track of the threads waiting to be notified and the mutex associated with the condition.

The wait() function for waiting on a condition variable notification requires a mutex as a parameter because it needs to unlock the mutex before suspending the process. Upon receiving the signal, it has to acquire the mutex in order to re-test the condition.

Specifically, the wait() function performs these steps:

- atomically:

- release mutex

- add self to condition variable’s wait queue

- sleep until notification

- after receiving signal:

- remove self from condition variable’s wait queue

- re-acquire lock

- return

It’s important to re-test the condition after waking up from a wait() to ensure that the condition has indeed been met, in case it was previously met but no longer holds, or in case of spurious wake-ups.

A spurious wake-up is when a thread is woken up knowing that it may not be able to proceed. This can happen if a signal occurs while the lock is still held. If the signaling doesn’t depend on the mutex-guarded data, it can be done after the lock is released.

It’s possible to have multiple readers OR a single writer by mutex-protecting a counter used for keeping track of whether there is a writer or how many readers there are. The actual read or write code is not protected by a lock to allow for multiple readers.

// GLOBAL

mutex counter_mutex;

condition_variable read_phase, write_phase;

int resource_counter = 0;

// READERS

lock (counter_mutex) {

// -1 means writer exists

while (resource_counter == -1) {

wait(counter_mutex, read_phase);

}

resource_counter++;

}

// READ DATA

// unlock

lock (counter_mutex) {

resource_counter--;

if (readers == 0) {

signal(write_phase);

}

}

// WRITER

lock (counter_mutex) {

while (resource_counter != 0) {

wait(counter_mutex, write_phase);

}

// -1 means writer

resource_counter = -1;

}

// WRITE DATA

// unlock

lock (counter_mutex) {

resource_counter = 0;

// signal readers first to give them a chance

broadcast(read_phase);

signal(write_phase);

}

Semaphores

Semaphores are a synchronization primitive represented by a count. Acquisition of a semaphore is represented by decrementing the count; imagine it as acquiring one of the resources the semaphore is controlling access to. When the count reaches 0 (i.e. no remaining resources), any other process which attempts to acquire the semaphore blocks until the count goes above 0.

To attempt to acquire a semaphore is to wait on the semaphore and releasing a semaphore is to post the semaphore. This corresponds to system calls sem_wait() and sem_post().

Semaphores can be used to synchronize shared memory access by having the writer and reader decrement/acquire the semaphore before the critical section and incrementing/releasing the semaphore after.

Read-Write Locks

A read-write locks is one which allows shared read access but exclusive write access. That is, if there is a writer then there can be no other writer or reader. If there is a reader, there can be many other readers.

Barriers

Barriers are a synchronization construct that are essentially the reverse of a semaphore. All threads wait at the barrier until all other threads have reached it, then they continue.

Atomics

Atomic instructions are ones which provide atomicity and mutual exclusion. They are atomic because either the whole operation succeeds or not at all. They provide mutual exclusion because several atomic instructions are queued up and executed sequentially, and not concurrently.

Inter-Process Communication

The physical pages that back a shared memory buffer aren’t necessarily contiguous.

There is a trade-off between sending messages (copy the data) and sharing memory (map the data). Since there is a non-negligible upfront cost to mapping memory into both process’ virtual address spaces, it can be much faster to simply send messages (copy the data) for small payloads. Otherwise, for much larger data it is definitely more efficient to map data.

Shared Memory

The kernel places limits on the number of segments and total size of System V shared memory, e.g. 4096 on modern kernels.

When a System V shared memory segment is created, the kernel returns an identifier so that other processes can attach the shared memory region to their virtual address space.

When a process no longer requires a System V shared memory segment, it should detach it, which invalidates the virtual address mappings for that memory region. The shared memory segment won’t be deallocated until a process explicitly requests that the kernel destroy it, otherwise it will continue to exist even if no processes use it.

Instead of shared memory segments from System V, POSIX shared memory uses files that reside in memory (tmpfs), therefore all operations are done on file descriptors. POSIX shared memory can be attached with mmap() and detached with unmmap().

Message Queues

Message queues can be used to synchronize shared memory access by having the writer send a “ready” message after writing to shared memory, with the reader responding with “ok” to acknowledge that it has read the data.

Signals

Signals can be sent to a process via kill(). A normal process can only send a signal to another process if the real or effective user ID of the sending process matches the real user ID or saved-set-user-ID of the receiving process. The effective user ID of the receiving process is not consulted to prevent one user from sending signals to another user’s process that is running a set-user-ID program belonging to the user trying to send the signal.

A signal mask is the set of signals whose delivery to the process is currently blocked. Signals are added and removed from the mask via sigprocmask(). If a signal is received while blocked, it remains pending, but is not queued, so that another signal of the same kind may “overwrite” it. The sigpending() call can retrieve the signal set identifying signals that it has pending.

Contrary to this, real-time signals are queued so that handlers are called the correct amount of times.

The sigsuspend() call can atomically modify the process signal mask and suspend execution until a signal arrives, which is essential to avoid race conditions when unblocking a signal and then suspending execution until that signal arrives, since it may have arrived in-between.

Re-entrancy affects how one can update global variables and limits the set of functions that can safely be called from a signal handler.

If a signal handler interrupts a blocked system call, the call returns EINTR. The call can be manually restarted or the signal handler can be established with SA_RESTART to cause many, but not all, system calls to automatically restart.

A one-shot signal is one that explicitly sets the signal handler which is then removed once handled.

A deadlock can occur if a signal handler attempts to acquire a lock that is already held by the interrupted/handling thread. The same can happen with interrupt handlers.

Interrupts

An interrupt is an event generated externally by components other than the CPU that receives it asynchronously, components such as I/O devices, timers, or other CPUs.

Interrupt masks apply to CPUs, since interrupts are received by CPUs, and can be used to control which CPUs to ignore or allow.

Interrupt handlers are set by the kernel for the entire system, compared to signal handlers which are set on a per-process basis.

When a device wants to send a notification to a CPU it sends an interrupt, for example via message signal interrupt (MSI).

Interrupts are uniquely identified based on the pins on which the interrupt occurs, or the MSI message.

When an interrupt is received by a CPU, the CPU looks up the interrupt identifier int he interrupt handler table to obtain the interrupt handler’s start address, then jumps to that location to begin executing the handler.

On multi-core systems, interrupts are only delivered to the CPUs that have them enabled. It can be beneficial to specify that only one CPU handles interrupts and block interrupts on all other CPUs using the interrupt mask, in order to avoid the overhead of handling interrupts on each core.

Interrupt handlers can be run on a separate thread, which avoids the possibility of deadlocks if the handler needs to acquire a mutex. If the handler doesn’t need to acquire any locks then it’ll simply execute on the interrupted thread’s stack.

The top-half of an interrupt handler refers to the part that is fast, non-blocking, and performs the minimum amount of processing. It should execute immediately when the interrupt occurs.

The bottom-half of an interrupt handler refers to the part that can contain arbitrary complexity and executes on a separate thread.

To minimize the cost of thread creation, the kernel may pre-create and pre-initialize thread structures for interrupt routines.

Networking

A common optimization is that if the kernel recognizes that the end-point network sockets of some connection both reside on the local system, the network bypasses the full protocol stack.

Virtualization

Virtualization is a way to allow concurrent execution of multiple operating systems and their applications on the same physical machine. A virtual machine (VM) is an operating system, its applications, and virtual resources. Virtual resources are subsets of hardware resources that a virtual machine believes that it owns.

A virtualization layer (aka virtual machine monitor (VMM), aka hypervisor) provides an environment to virtual machines that closely resembles the host machine, with only a minor decrease in speed. It manages access of the system resources to the virtual machines, providing safety and isolation.

It’s important to understand that guest VM instructions are executed directly by the hardware, they are not emulated.

Virtualization provides consolidation so that multiple virtual machines can run on a single physical platform, decreasing costs and improving manageability. It also provides migration, increasing encapsulation, availability, and reliability. Virtualization provides security containment. It also improves debuggability, and allows legacy operating systems to run where otherwise the hardware required may not be easily accessible.

The two main models of virtualization are Type 1: base-metal/hypervisor, and Type 2: hosted.

Isolation of VMs can be provided by having the hypervisor utilize protection modes and levels/rings to compartmentalize the hypervisor and guest VMs. Specifically, the hypervisor can use root protection mode with ring0 protection level, whereas the non-root VMs can use non-root protection mode and ring0 for the VM’s operating system and ring3 for the VM’s applications.

When a guest VM running at ring0 in non-root mode runs certain instructions that are only accessible by root mode, it causes a VMexit which triggers a switch to root mode, after which control is passed to the hypervisor. When the hypervisor is done, it performs a VMentry to switch back to non-root mode, after which control is returned to the VM. This sequence may be initiated as a result of a hypercall, which is essentially the system call analogue to hypervisors, i.e. a system call to the hypervisor.

Trap-and-emulate is a way for privileged operations to trap into the hypervisor. If the operation is illegal, the VM is terminated, otherwise the expected behavior is emulated by the hypervisor for the guest.

Dynamic binary translation consists of modifying the guest VM code as it’s running. In particular, it inspects code blocks to be executed and if necessary, translates them into an alternate instruction sequence, such as to emulate the desired behavior (possibly even avoiding a trap). Otherwise the code block runs directly, at hardware speeds.

Device Virtualization

The pass-through model of virtualization is one where a hypervisor-level driver configures device access permissions so that a VM can be given exclusive, direct access to a device, completely bypassing the hypervisor. This is useful for example to give a VM direct access to the mapped memory of a device, such as NIC.

The hypervisor-direct model of virtualization is one where the hypervisor intercepts all device accesses performed by a guest. The device operation can then be emulated. For example, the device access can be translated to a generic representation of the I/O operation, sent up the hypervisor-resident I/O stack, and used to invoke the hypervisor-resident driver. This way the VM is decoupled from the physical device so that sharing and migration becomes easier, for example. This adds latency, however.

The split-device driver model of virtualization is one where device access control is split between a front-end driver in the guest VM (device API) and a back-end driver in the service VM or host. This only applies to paravirtualized guests because the front-end driver needs to interface with the back-end driver. This eliminates emulation overhead because there’s no need to guess what the guest OS is trying to do, since the guest OS explicitly specifies what it needs to do. This also allows for better management of shared devices.

One way to reclaim memory from a guest VM is to install a balloon driver which is given commands by the hypervisor. When memory needs to be reclaimed from the VM, the balloon is told to “inflate” which causes memory to be paged out to disk in order to give the balloon enough memory. Once the memory has been pushed to disk, it can be returned to the hypervisor. Conversely, this can also be used to release memory to the guest VM by instructing the balloon driver to reduce its memory footprint, leaving the rest of the guest VM more memory to use.

Memory pages can be shared between multiple virtual machines via VM-oblivious page sharing, in which the hypervisor maintains a hash table indexed by the page contents. If a page matches an existing entry in the hash table, a full comparison of the pages is done to make certain that there is a match, since the entry in the table can represent a page that has since been modified. If there’s indeed a match, then the pages are made to map to the same machine page, the reference count in the hash table entry is incremented, the page is marked Copy-on-Write, and the old page can be freed. This should be done in the background when there is light load, as with compaction/defragmentation.

Full Virtualization

Full virtualization is when the guest operating system runs as-is without modification.

In full virtualization, memory virtualization provides all guests with an appearance of contiguous physical memory starting at physical address 0. Conceptually, this requires three different kinds of addresses and page frame numbers:

- virtual addresses: used by applications in the guests

- physical addresses: those that the guest thinks are the physical addresses

- machine addresses: the actual physical addresses

One way of providing memory virtualization is to have the guest OS page tables map virtual-to-physical addresses, and have the hypervisor’s page tables map physical-to-machine addresses. However, this can be expensive since it introduces another layer to address translation.

Another option is to have the hypervisor maintain a shadow page table of virtual-to-machine addresses which can be used by the MMU. It can write-protect the guest OS page table to track new mappings, but it must then be invalidated on context-switch since the virtual addresses will no longer be valid.

Paravirtualization

Paravirtualization works by modifying the guest operating system so that it becomes aware of the fact that it is being virtualized. The guest OS can make explicit calls to the hypervisor (hypercalls) which trap into the hypervisor. This is used by Xen.

Memory virtualization is achieved explicitly. The guest OS can explicitly register page tables with the hypervisor, since it’s aware that it is being virtualized. The guest must not have write permissions for the page table, since that would circumvent isolation. This means that each update requires a trap to the hypervisor, so that the hypervisor can mediate the process.

Hypervisor-based Virtualization

In Type 1 bare-metal/hypervisor-based virtualization, a virtual machine monitor (VMM)/hypervisor manages all hardware resources and execution of VMs by running a privileged service VM which manages the physical hardware resources directly. This privileged service VM runs a “regular” operating systems which has the necessary device drivers, which avoids requiring each VM to have device drivers for the particular operating system running on that VM.

Examples of hypervisor-based virtualization include Xen and VMware ESX. In Xen, virtual machines are called domains (DomU’s), and the privileged service VM (domain) which runs the drivers is dom0 (domain zero). Xen is the actual hypervisor. With VMware ESX, a dedicated service VM that runs drivers isn’t as necessary because drivers are made specifically for ESX by many hardware vendors due to VMware’s market share.

Hosted Virtualization

In Type 2 hosted virtualization, the host operating system owns all of the hardware and it has a special virtual machine monitor (VMM) module which produces hardware interfaces to VMs and handles VM context switching. This can leverage all services and features of the host operating system, avoiding the need to reinvent functionality as in a hypervisor.

An example of hosted virtualization is Kernel-based VM (KVM) which transforms the host operating system into a hypervisor-like mode. Guest VMs are run via QEMU in virtualizer mode.

Live Migration

Checkpointing can be useful in the area of virtualization so that a virtual machine can be transferred to another server so that the original host can be brought down for maintenance, for example. In this context, the process is referred to as live migration.

The warm-up phase of a pre-copy memory migration of a virtual machine consists of copying all of its memory from the source to the destination while the VM is still running, while continuously re-copying dirtied pages until the rate of re-copied pages is greater-than-or-equal-to the page dirtying rate.

Once this condition is met, the stop-and-copy phase of a pre-copy memory migration begins. The VM is stopped in order to copy the (relatively few) remaining dirty pages to the destination. Then the VM is resumed at the destination.

In this pre-copy memory migration process, the down-time is equal to the time between stopping the VM at the source and resuming it at the destination.

-

Perhaps by making the file offsets a single atomic offset? Check. ↩︎

-

This reminds me of how log-structured merge trees (LSM-trees) are also used by some databases to reduce random access. ↩︎

-

This reminds me of distributed systems, where some systems decide to execute sequentially in the interest of avoiding race conditions. ↩︎

-

This reminds me of the

wait()call on condition variables, where the condition is checked after a wake-up to ensure that the condition still holds. ↩︎