Networking

Switching

The Address Resolution Protocol (ARP) can be used to obtain the MAC address of a given IP address. It does this by broadcasting a query to which the matching target IP address responds with the IP address via unicast. A mapping for that IP address to that MAC address is then added to the ARP table.

When a host on a hub-interconnected LAN wants to send a packet to another host on the same hub, it does so by broadcasting the packet to every host. This has the disadvantage of potentially flooding the network, which increases the chance for the collision of frames, which increases latency because collisions require other hosts to back off and not send anything when they see that other senders are trying to send at the same time.

Switches provide traffic isolation by partitioning the LAN into separate LAN segments known as broadcast domains so that a frame bound to a host on the same LAN segment isn’t forwarded to other LAN segments. In order to prevent frames from being broadcast to irrelevant LAN segments, the learning switch must maintain state such as a forwarding table which maps the destination MAC address to the output port (i.e. broadcast domain).

In a learning switch, when host A sends a frame to host B and the forwarding temple is empty, it will insert an entry mapping host A’s MAC address to output port (broadcast domain), then floods (broadcasts) the frame to all other ports.

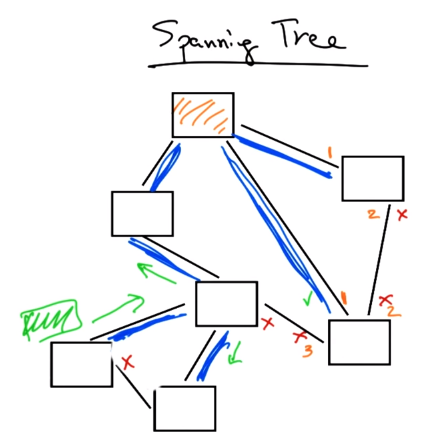

Cycles in the underlying physical network topology can create the potential for learning switches to introduce forwarding loops and broadcast storms. To prevent this, the switch must construct a spanning tree of the network topology so that packets are only forwarded along the spanning tree.

The spanning tree of the network topology can be constructed in a distributed manner by the switches by electing a leader/root (e.g. switch with smallest ID) and at each switch, excluding the link/port if it’s not the shortest path to the root.

In the image below, the top orange node is the root. The blue links are part of the spanning tree. Some links have the distance to the root shown in orange.

To determine the root of the spanning tree, switches run an election process to determine the switch with the smallest ID. Whenever a switch learns of another switch with a smaller ID, it updates its view of the root, computing the distance to that new root. This way when neighbors receive this new information, they can determine their distance to the new root by adding one to the neighboring node’s distance to the root.

Routing

The differences between switches and routers are as follows:

- switches:

- typically operate at layer 2 (ethernet)

- auto-configuring

- forwarding tends to be fast

- limitation: broadcasts (spanning tree, ARP queries)

- routers:

- typically operate at layer 3 (IP)

- not restricted to a spanning tree

Intradomain routing concerns routing within a single autonomous system, whereas interdomain routing concerns routing between autonomous systems.

A point of presence (POP) is a node in a dense population center, closer to other POPs and customers.

A larger buffer on a switch or router means that there can be a larger queuing delay, which means that it will take longer for the source to hear about congestion that might exist on the network.

The rule of thumb for the ideal buffer size for switches and routers is that the buffer size should be equal to the maximum amount of outstanding data that can be on the path between the source and destination, i.e. $2T \cdot C$, where $2T$ is the roundtrip propagation delay and $C$ is the capacity of the bottleneck link.

There is a revised recommended buffer size which accounts of the number of flows $n$ passing through the router:

In distance vector routing, each router sends multiple distance vectors to each of its neighbors, essentially copies of its own routing table. Routers then compute the costs to each destination based on the shortest available path, often using Bellman-Ford, and update their routing tables. These updated tables are then sent to their neighbors again until convergence.

For example, if node $x$ is trying to find a shortest-cost route to node $y$ through some intermediate node $v$, the shortest-cost is the minimum of the costs to each intermediate node $v$ plus $v$’s distance to $y$.

Split horizon ensures that updates received on an interface are not sent back on the same interface they were received on, preventing loops.

The count to infinity problem is when the cost of a link changes but a neighbor chooses to reach a destination by visiting the node and reversing. Poison reverse prevents this by actively advertising a route as unreachable over the interface over which it was learned. For example, in the following network:

If A learns about the distance to C from B, A will make sure to advertise to B the distance to C as infinity/unreachable. This way if the link between B and C goes down, B won’t try to reach C through A, which would only loop back to B thus creating an infinite loop.

Transmission Control Protocol

A TCP sender’s sending rate $R$ is defined as: