Haskell

I originally chose Erlang as the first functional programming language to attempt learning. However, the combination of different programming paradigm, obscure Prolog-like syntax, and unfamiliar concurrency paradigm made it particularly difficult for me to see the big picture of functional programming.

I’m actually familiar with Haskell now. This very site is written in Haskell, and I have worked on a few other Haskell projects. That said, Haskell is also a programming language theory (PLT) playground. To that end, GHC contains various Haskell language extensions which I’m not entirely familiar with. This page of notes will therefore not necessarily cover the more basic aspects and instead will cover language extensions, popular libraries, idiomatic patterns, modules, parallelism and concurrency, and so on.

User Guide

It’s possible to build an EPUB eBook of the GHC User Guide. You’ll need to have the required dependencies to build the documentation. In my experience I ended up having to boot an Ubuntu VM because the xsltproc packages on arch were too new. It’s necessary to build the documentation at least once to generate the necessary files, which unfortunately ends up building GHC itself it seems. See this IBM article for more information on building eBooks with docbook.

$ ./configure

$ cd docs/users_guide

$ make html stage=0 FAST=YES

$ cd ..

$ /usr/bin/xsltproc \

> --stringparam base.dir docs/users_guide/users_guide/ \

> --stringparam use.id.as.filename 1 \

> --stringparam html.stylesheet fptools.css \

> --nonet \

> --stringparam toc.section.depth 3 \

> --stringparam section.autolabel 1 \

> --stringparam section.label.includes.component.label 1 \

> http://docbook.sourceforge.net/release/xsl/current/epub3/chunk.xsl \

> docs/users_guide/users_guide.xml

$ cd docs/users_guide

$ rm *.html

$ echo "application/epub+zip" > mimetype

$ zip -0Xq ghc.epub mimetype

$ zip -Xr9D ghc.epub *

$ stat ghc.epub

Type Classes

Many types can be reasoned about with a core set of type classes. This section goes over the typeclassopedia.

Functors

A functor represents a computational context. The functor laws ensure that the fmap operation doesn’t change the structure of the container, only its elements. The functor laws aren’t enforced at the type level. Actually, satisfying the first law automatically satisfies the second.

class Functor f where

fmap :: (a -> b) -> f a -> f b

-- functor laws

fmap id = id

fmap (g . h) = (fmap g) . (fmap h)

A way of thinking of fmap is that it lifts a function into one that operates over contexts. This is evident from the type signature that explicitly emphasizes the fact that it is partially applied.

fmap :: (a -> b) -> f a -> f b

fmap :: (a -> b) -> (f a -> f b)

g :: a -> b

fmap g :: f a -> f b

Applicative Functors

Applicative functors lie somewhere between functors and monads in expressivity. While functors allow the lifting of a normal function to a function on a computational context, applicative functors allow for the application of a function within a computational context. The type class includes a function pure for embedding values in a default, effect free context. Applicatives are functors by definition.

class Functor f => Applicative f where

pure :: a -> f a

(<*>) :: f (a -> b) -> f a -> f b

The <*> function is essentially function application within a computational context.

($) :: (a -> b) -> a -> b

(<*>) :: f (a -> b) -> f a -> f b

It’s straightforward enough to create a convenient infix function that can be used like the regular function application $ by embedding a regular function in a computational context before applying it to the parameter:

(<$>) :: (a -> b) -> f a -> f b

(<$>) g x = pure g <*> x

However, this is what fmap already does based on its type. For this reason, the <$> convenience function is simply an infix alias for fmap.

fmap :: (a -> b) -> f a -> f b

(<$>) :: (a -> b) -> f a -> f b

(<$>) = fmap

Note that in a monadic context, the effects are applied sequentially, from left to right. This is makes sense because function application is left-associative, and each application of <*>, which for monads is ap which itself is liftM2 id, has to extract the pure function and value from their respective monad ‘container’ 1, thereby performing the monad’s effects.

There also exists functions *> and <* that sequence actions while discarding the value of one of the arguments: left and right respectively. These are immensely useful for monadic parser combinators such as those found in the Parsec library. For example, *> is useful in Parsec to consume the first parser but return the second, similar to >> in a monadic context.

(*>) :: f a -> f b -> f b

u *> v = pure (const id) <*> u <*> v

(<*) :: f a -> f b -> f a

u <* v = pure const <*> u <*> v

Finally, there’s a function that replaces all of the locations in the input context with the provided value. This is useful in Parsec when we want to parse some input, and if the input is successfully consumed, return something else, such as parsing a URL-encoded space with ' ' <$ char '+'.

(<$) :: a -> f b -> f a

(<$) = fmap . const

-- (fmap . const) x y

-- ((fmap . const) x) y

-- (fmap (const x)) y <- (f . g) x = f (g x)

-- fmap (const x) y

-- can also be thought of as

x <$ y = pure x <* y

Parallelism

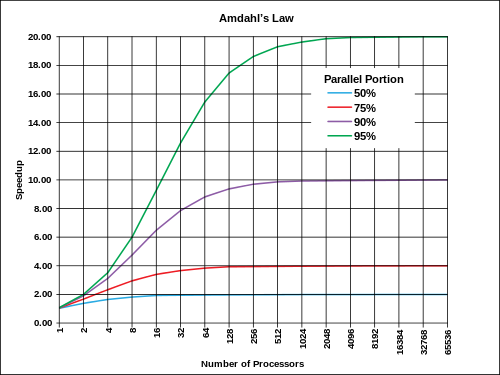

Amdahl’s law places an upper bound on potential speedup that may be available by adding more processors. The expected speedup $S$ can be described as a function of the number of processors $N$ and the percentage of runtime that can be parallelized $P$. The implications are that the potential speedup increasingly becomes negligible with the increase in processors, but more importantly that most programs have a theoretical maximum amount of parallelism.

ThreadScope

The ThreadScope tool helps visualize parallel execution, particularly for profiling. To use ThreadScope, the program should be compiled with the -eventlog GHC option and then run with the +RTS -l option to generate the eventlog. ThreadScope is then run on this event log:

$ ghc -O2 program.hs -threaded -rtsopts -eventlog

$ ./program +RTS -N2 -l

$ threadscope program.eventlog

Eval Monad

The Eval monad from Control.Parallel.Strategies expresses parallelism naturally. The rpar combinator expresses that the argument can be evaluated in parallel, and rseq forces sequential evaluation. Evaluation is to weak head normal form (WHNF), i.e. the outermost type constructor is evaluated. Notice that the monad is completely pure, with no need for the IO monad.

data Eval a

instance Monad Eval

runEval :: Eval a -> a

rpar :: a -> Eval a

rseq :: a -> Eval a

For example, the following evaluates two thunks in parallel then waits for both to be evaluated before returning:

runEval $ do

a <- rpar $ f x

b <- rpar $ f y

rseq a

rseq b

return (a, b)

Consider the following parallelized map implementation:

parMap :: (a -> b) -> [a] -> Eval [b]

parMap f [] = return []

parMap f (a:as) = do

b <- rpar (f a)

bs <- parMap f as

return (b:bs)

runEval $ parMap f xs

Sparks

An argument to rpar is called a spark. The runtime collects sparks in a pool and distributes them to available processors using a technique known as work stealing. These sparks are to be converted, i.e. evaluated in parallel, though this may fail in a variety of ways. The +RTS -s option provides information about the sparks and what became of them during the execution of the program in the following form:

SPARKS: 100 (100 converted, 0 overflowed, 0 dud, 0 GC'd, 0 fizzled)

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| converted | evaluated in parallel |

| overflowed | didn’t fit in the spark pool |

| dud | already evaluated, ignored |

| GC’d | unused, garbage collected |

| fizzled | evaluated some place else |

Deepseq

The Control.Deepseq module contains various utilities for forcing the evaluation of a thunk. It defines the NFData, i.e. normal-form data, type class. This type class has only one method, rnf, i.e. reduce to normal-form, which defines how the particular type may be evaluated to normal form, returning () afterward:

class NFData a where

rnf :: a -> ()

rnf a = a `seq` ()

The module also defines a deepseq function which performs a deep evaluation to normal form, similar to seq which performs shallow evaluation to WHNF. There’s also a more convenient force function which evaluates the argument to normal form and then returns the result.

deepseq :: NFData a => a -> b -> b

deepseq a b = rnf a `seq` b

force :: NFData a => a -> a

force x = x `deepseq` x

Evaluation Strategies

Evaluation strategies decouple algorithms from parallelism, allowing for parallelizing in different ways by substituting a different strategy. A Strategy is a function in Eval that returns its argument.

type Strategy a = a -> Eval a

A strategy would take a data structure as input which is then traversed and evaluated with parallelism and returns the original value. For example a strategy for evaluating a pair tuple could look like:

parPair :: Strategy (a, b)

parPair (a, b) = do

a' <- rpar a

b' <- rpar b

return (a', b')

This strategy could then be used either directly or using the using combinator, which reads as use this expression by evaluating it with this strategy:

using :: a -> Strategy a -> a

x `using` s = runEval (s x)

runEval . parPair $ (fib 35, fib 36)

(fib 35, fib 36) `using` parPair

Parameterized Strategies

The parPair always evaluates the pair components in parallel and always to WHNF. A parameterized strategy could take as arguments strategies to apply to the type’s components. The following evalPair function is so called because it no longer assume parallelism, instead delegating that decision to the passed in strategy.

evalPair :: Strategy a -> Strategy b -> Strategy (a, b)

evalPair sa sb (a, b) = do

a' <- sa a

b' <- sb b

return (a', b')

It’s then possible to define a parPair function in terms of evalPair that evaluates the pair’s components in parallel. However, the rpar strategy only evaluates to WHNF, restricting the evaluation strategy. We could instead use rdeepseq—a strategy to evaluate to normal form—by wrapping rdeepseq with rpar. The rparWith combinator allows the wrapping of strategies in this manner:

rdeepseq :: NFData a => Strategy a

rdeepseq x = rseq (force x)

rparWith :: Strategy a -> Strategy a

parPair :: Strategy a -> Strategy b -> Strategy (a, b)

parPair sa sb = evalPair (rparWith sa) (rparWith sb)

This then allows us to use parPair to create a strategy that evaluates a pair tuple to normal form, which can then be used with the using combinator:

(fib 35, fib 36) `using` parPair rdeepseq rdeepseq

Sometimes it may be required to not evaluate certain type components, which can be accomplished using the r0 strategy. For example, the following evaluates only the first components of a pair of pairs, i.e. a and c:

r0 :: Strategy a

r0 x = return x

evalPair (evalPair rpar r0) (evalPair rpar r0) :: Strategy ((a, b), (c, d))

The parMap function can be defined in terms of evaluation strategies. The parList function is a strategy that evaluates list elements in parallel. Defining parList can take the same approach as before: define a parameterized strategy on lists called evalList and then define a parameterized function parList that performs evalList in parallel. Both of these functions are already defined in Control.Parallel.Strategies:

evalList :: Strategy a -> Strategy [a]

evalList strat [] = return []

evalList strat (x:xs) = do

x' <- strat x

xs' <- evalList strat xs

return (x':xs')

parList :: Strategy a -> Strategy [a]

parList strat = evalList $ rparWith strat

parMap :: (a -> b) -> [a] -> [b]

parMap f xs = map f xs `using` parList rseq

Documentation

Haddock is the documentation system that is most prevalent in the Haskell community. Documentation can be generated using the haddock command or more commonly cabal haddock.

Declarations can be annotated by beginning comments with -- |, which applies the documentation to the following declaration in the source file. It’s also possible to place annotations after a given declaration, in which case the caret ^ is used instead of the | to denote an annotation.

data T a b

-- | the C1 constructor is used for foo

= C1 a b

-- | the C2 constructor is used for bar

| C2 a b

data T a b

= C1 a b -- ^ the C1 constructor is used for foo

| C2 a b -- ^ the C2 constructor is used for bar

Annotations can span multiple lines until the first non-comment line is encountered. It’s also possible to use multi-line comments by opening them with {-|.

-- | this is a comment

-- that spans multiple lines

f :: Int -- ^ the int

-> Float -- ^ the float

-> IO () -- ^ the return value

Chunks of documentation can be given a name with $name and then included elsewhere.

module Foo (

-- $doc

)

-- $doc

-- this is a large chunk of documentation

-- that spans many lines

Haddock Markup

One or more blank lines separates two paragraphs. Emphasis is denoted by surrounding text with a forward-slash /, whereas bold text is denoted by surrounding the text with two underscores __ Monospace text is denoted by surrounding it with @. Other markup is valid inside each of these, for example, @'f' will hyperlink the identifier f within the monospace text.

Links can be inserted using <url label> syntax, although Haddock automatically links free-standing URLs. It’s also possible to link to other parts of the same page with #anchor# syntax.

Images can be embedded with <<path.png title>> syntax.

It’s possible to link to Haskell identifiers that are types, classes, constructors, or functions by surrounding them with single quotes. If the target is not in the scope, they may be referenced by fully qualifying them.

-- | This module defines the type 'T'

-- It has nothing to do with 'M.T'

Alternatively, it’s possible to link to a module entirely by surrounding the name with double quotes.

-- | This is a reference to the "Foo" module

Code blocks may be inserted by surrounding the paragraph with @ signs, where its content is interpreted as normal markup. Alternatively, it’s possible to do so by preceding each line with a >, in which case the text is interpreted literally.

-- | this is some documentation that includes code

--

-- @

-- f x = x + x

-- @

--

-- > g x = x * 42

It’s possible to denote REPL examples with >>>, followed by the result.

-- | demonstrating the REPL example syntax

--

-- >>> fib 10

-- 55

Unordered lists are possible by simply preceding the paragraph with a * or -. Ordered lists are possible by preceding each item with (n) or n..

Haddock Options

Haddock accepts some comma-separated list of options that affect how it generates documentation for that module, much like LANGUAGE pragmas in Haskell.

{-# OPTIONS_HADDOCK hide, prune #-}

| Option | Effect |

|---|---|

| hide | omits module; doesn’t affect re-exported definitions |

| prune | omits definitions with no annotations |

| ignore-exports | ignore export list; all top-level declarations are exported |

| not-home | module shouldn’t be considered to be home module |

| show-extensions | include all language extensions used in the module |

GHC Extensions

Haskell is a PLT playground, and as a result GHC has available a multitude of language extensions. I found a series of articles that cover some of the more popular extensions.

Named-Field Puns

Record puns allows for the easy creation of bindings of the same name as their field.

{-# LANGUAGE NamedFieldPuns #-}

greet IndividualR { person = PersonR { firstName = fn } } = "Hi, " ++ fn

greet IndividualR { person = Person { firstName } } = "Hi, " ++ firstName

Record WildCards

This extension allows the use of two dots .. to automatically create bindings for all fields at that location, named the same as the fields they bind.

{-# LANGUAGE RecordWildCards #-}

greet IndividualR { person = PersonR { .. } } = "Hi, " ++ firstName

Tuple Sections

Tuple sections are a straightforward extension that allows tuples to be used in sections.

{-# LANGUAGE TupleSections #-}

(1, "hello",, Just (),) == \x y -> (1, "hello", x, Just (), y)

Package Imports

This allows one to explicitly specify the package from which to import a module, which is useful when needed for disambiguation purposes.

{-# LANGUAGE PackageImports #-}

import "package-one-0.1.01" Data.Module.X

import qualified "containers" Data.Map as Map

Overloaded Strings

This allows string literals to be polymorphic over the IsString type class which is implemented by types like Text and ByteString, making it less of a pain to construct values of those types.

{-# LANGUAGE OverloadedStrings #-}

import qualified Data.Text.IO as T

main = T.putStrLn "Hello as Text!"

Lambda Case

This provides a shorthand for a lambda containing a case match.

{-# LANGUAGE LambdaCase #-}

\x -> case x of == \case

Multi-Way If

This allows guard syntax to be used with if expressions to avoid excessive nesting and repeating of the if expression.

{-# LANGUAGE MultiWayIf #-}

if | x == 1 -> "a"

| y < 2 -> "b"

| otherwise -> "d"

Bang Patterns

This allows to evaluate to a value to weak head normal form before matching it.

{-# LANGUAGE BangPatterns #-}

strictFunc !v = ()

View Patterns

A view pattern e -> p applies the view e to the argument that would be matched, yielding a result which is matched against p.

{-# LANGUAGE ViewPatterns #-}

eitherEndIsZero :: [Int] -> Bool

eitherEndIsZero (head -> 0) = True

eitherEndIsZero (last -> 0) = True

eitherEndIsZero _ = False

Pattern Guards

Pattern guards are a generalization of guards which allow pattern guardlets aside from the more common boolean guardlets. Pattern guardlets are of the form p <- e which is fulfilled (i.e. accepted) when e matches against p. Further guardlets can be chained with commas. As usual, guardlets are tested in order from top to bottom before the guard as a whole is accepted.

{-# LANGUAGE PatternGuards #-}

func :: [Int] -> Ordering

func xs | 7 <- sum xs -- if the sum is 7

, n <- length xs -- bind the length to n for further checks

, n >= 5 -- and the length is >= 5

, n <= 20 -- and <= 20

= EQ -- then evaluate to EQ

| otherwise

= LT

Explicit Universal Quantification

This allows to explicitly annotate universal quantification in polymorphic type signatures. On its own this extension isn’t very useful. Instead, it’s required by many other extensions.

{-# LANGUAGE ExplicitForAll #-}

map :: forall a b. (a -> b) -> [a] -> [b]

Scoped Type Variables

This allows type variables to have scope so that nested scopes’ type signatures can close over them and refer to them. Without the extension, the a in the type signature of sorted and nubbed would not only be different from func’s type signature, but also different from themselves.

{-# LANGUAGE ScopedTypeVariables #-}

func :: forall a. Ord a => [a] -> [(Char, a, a)]

func xs = zip3 ['a' .. 'z'] sorted nubbed

where sorted :: [a]

sorted = sort xs

nubbed :: [a]

nubbed = nub xs

Liberal Type Synonyms

This relaxes restrictions on type synonyms so that type signatures are checked until after all type synonyms have been expanded, so that something like this is possible:

{-# LANGUAGE LiberalTypeSynonyms #-}

type Const a b = a

type Id a = a

type NatApp f g i = f i -> g i

func :: NatApp Id (Const Int) Char

-- Id Char -> Const Int Char

-- Char -> Int

func = ord

Rank-N Types

This allows the nesting of explicit universal quantifications within function types and data definitions. In the following example, the difference between the signatures is that the first signature specifically applies the universal quantification to the passed in function, whereas the second signature applies the universal quantification to the whole signature.

What this means is that the second signature would accept any function from n -> n that applies for some Num n, but the first signature requires a function from n -> n that applies for every Num n.

For example, (+1) would be valid for both signatures, since every Num defines (+). However, (/5) would only be valid for the second signature because it’s a function from n -> n that only applies for some Num n, particularly the subset of Num n that also implements Fractional. Since not every Num n implements Fractional, that function is not valid for the first signature.

Note: This extension deprecates the less general extensions Rank2Types and PolymorphicComponents.

{-# LANGUAGE RankNTypes #-}

rankN :: (forall n. Num n => n -> n) -> (Int, Double)

rankN f = (f 1, f 1.0)

-- compare to

rankN :: forall n. Num n => (n -> n) -> (Int, Double)

When this extension is used in conjunction with LiberalTypeSynonyms, it allows the universal quantification and/or constraints within type synonyms as well as the application or partial application of a type synonym to a type containing universal quantification and/or constraints.

type Const a b = a

type Id a = a

type Indexed f g = forall i. f i -> g i

type ShowIndexed f g = forall i. (Show i) => f i -> g i

type ShowConstrained f a = (Show a) => f a

type FunctionTo a b = b -> a

func1 :: Indexed Id (Const Int)

-- forall i. Id i -> Const Int i

-- forall i. i -> Int

func1 _ = 2

func2 :: ShowIndexed Id (Const Int)

-- forall i. (Show i) => Id i -> Const Int i

-- forall i. (Show i) => i -> Int

func2 = length . show

func3 :: forall a. ShowConstrained (FunctionTo Char) a

-- forall a. (Show a) => FunctionTo Char a

-- forall a. (Show a) => a -> Char

func3 = head . show

type ShowConstrained2 f = forall a. (Show a) => f a

type EnumFunctionTo b a = (Enum a) => a -> b

func :: ShowConstrained2 (EnumFunctionTo Char)

-- forall a. (Show a) => EnumFunctionTo Char a

-- forall a. (Show a, Enum a) => a -> Char

func = head . show . succ

Empty Data Declarations

This allows the definition of types with no constructors, which is useful for use as a phantom parameter to some other type.

data Empty

data EmptyWithPhantom x

type EmptyWithEmpty = EmptyWithPhantom Empty

Phantom Types

Phantom types are parameterized types where some of the parameters only appear on the RHS. They are often used to encode information at the type level to make code much more strict, usually paired with empty data types.

Consider an API for sending encrypted messages. It’s possible to encode—at the type-system level—that only encrypted messages may be sent using the send function, thus preventing plain-text messages from being sent. This is further enforced by making the Message constructor private and exposing a single constructor to build a plain-text message, such as newMessage.

data Message a = Message String

data Encrypted

data PlainText

send :: Message Encrypted -> Recipient -> IO ()

encrypt :: Message PlainText -> Message Encrypted

decrypt :: Message Encrypted -> Message PlainText

newMessage :: String -> Message PlainText

newMessage s = Message s

-- this would not type-check

send (newMessage "test") "recipient@server"

Resources

- Categories from Scratch

- Category Theory on Youtube

- What I Wish I Knew

- Learning Haskell

- CS 194

- Performance profiling with ghc-events-analyze

- Haskell Wikibooks - Category Theory

- Getting it Done with Haskell